Being Low(er) Income In Effective Altruism

There have been a series of discussions on EA forums about representation of minorities and marginalized groups. I will be writing several posts about this topic.

One proposed way to increase donations and charitable giving is to destigmatize discussions of money and giving. We do this because when we discuss our behavior with others it creates a standard of conduct within our communities. When we review and examine our charitable donations it reminds our friends and family the importance of giving and creates a norm around increasing donations as well as support and praise for giving. The goal being to create a culture of positive reinforcement and praise. So we are working on building a culture that is OK talking about money because we believe that this has the potential to do a lot of good, even though it may be uncomfortable at first.

But these discussions can be super uncomfortable if you know you can't donate at that same level. So it becomes easy to see why going to a meet-up or discussion where people are talking about how to donate large sums of money is something people of lower income would avoid.

A few months ago at an EA meetup, the question was asked if everyone in the group was a tech worker. At the time I didn't volunteer being the only non-techy in the room. One because I was interested in other people's response, but mainly because I was overcome with my latent desire not to draw attention to myself. I also had a suspicion that had I thrown my hand up I would have gotten questions about what I do (which I don't think is very interesting), or worse *eep* why I'm not earning to give.

The several people in the room that know I don't work as a programer, or anywhere around the tech industry, also didn't volunteer that I wasn't 'one of them.' This experience was interesting, not just because of my amusement at my own shyness, but because it exemplifies something that I've heard others mention about being around a lot of effective altruists. The group has a tendency to be be mostly homogenous in nature, which can be ostracizing for those that don't necessarily fit.

Most of the male, techy, analytical types that inhabit the EA space have very high earning potential. More than that, they start out with at pretty good pay rate. The Seattle group is mainly late 20s, early 30s working professionals. Which means most of our members are already earning a good salary and even earning to give, while comfortably paying off what student debt they have.

I do not fit this mold. Read: I'm broke.

I earn a decent salary now for an entry level admin job. But I graduated college as the market crashed in 2009. I have debt with high interest. I have the support of a great family, but we have always lived paycheck to paycheck. I chose to work in a field that does not pay well. I live in an expensive city. All this culminates to mean that every month I run my finances through the calculator. It means that frequently my bank account reads $3 for a day or two before my paycheck. It means I have to budget in coffee dates and doctor visits.

“When I’m surrounded by people I know earn enough to give away 10% of their income and still not sweat buying dinner for 7 people I feel out of place*”

All this means that I am fairly consistently thinking about money. Not always stressed about it, but always thinking about it. I have the running tally sheet of expenses in my head, that gets pulled up every time someone suggests we grab dinner. It means I have a small constant drain on my thought process, on my decision making abilities, and my emotional stability.

It means that every time I organize a meet-up for EA I have to worry about who is paying for snacks. It means that I feel guilty eating dinner I know someone else paid for, even though I know the expense has very little impact on them. It means that I carry cash to pitch in whenever possible. This is partially because I fear standing out among my EA group*, but mostly because when you are lower income you value and count money closely.

And that seems like the main difference. I feel each dollar spent, even when it isn't my dollar.

When I'm surrounded by people I know earn enough to give away 10% of their income and still not sweat buying dinner for 7 people I feel out of place. I am in awe of being able to do that. I feel fully the fact that this simple difference puts me at a disadvantage to those around me*. And I wonder how to relate to these people I am supposed to be organizing, motivating, and advising.

I'm well aware of my own privilege and I know I not nearly as bad off as most low income people in this country. But the fact that I can feel so out of place at EA meetings, given the relatively low difference in income between myself and my peers, I realize that truly low income individuals would likely not feel comfortable in our group at all. And that makes me inexplicably sad.

As a culture we have a tenancy to brush over economic diversity when discussing inclusion. Sadly, I think this is because it is closely related with ethnic and racial diversity. Also because we just don't like to talk about money. I believe that effective altruism can feel very exclusionary to those of lower economic status, and that this group is incredibly underrepresented within EA (for a discussion of why homogeneity is detrimental see my previous posts about diversity).

“So we naturally don’t socialize with people that spend above our means.”

One reason why EA is lacking economic diversity is because we tend to naturally separate ourselves based on class; as I illustrate in my experiences above, it feels icky to not be able to keep up. So we naturally don't socialize with people that spend above our means. But this distinction, this other-ness becomes clearer and more prevalent when hanging around effective altruists because we value talking about money and how much we donate.

But this means we are missing a huge chunk of donors! Because people of lower income donate lots of money. Like this ineractive map, most of these references focus on percentage donated, which actually works out to slightly less money than the donations by larger donors. But the inclination for altruism seems stronger in lower and middle income individuals (perhaps because we feel each dollar spent). It may be worth considering that it is easier to convince someone who is already donating to change their charitable giving than it is to convince someone to start giving, or give more.

Perhaps beyond diversity, it may be more effective to be wooing lower income donors.

So I decided I would start raising my hand, and raising it higher. Now when the question goes out in groups if everyone is a tech worker I swing my hand up and practically yell "I'm not!" When I was talking with people about plans to attend EA Global I explicitly mentioned that money was my limiting factor. Even though it made me cringe each time I said it. Of course no one minded, and it meant I got some support from friends. But that isn't why I said it.

I point out my lack of money to other EA people now, not for myself, but for those who are not there. Those that have either felt excluded from, or never even heard of, EA specifically because of their income level. I own the fact I am lacking in funds so that our community stays cognizant of the fact that not everyone who cares about effectiveness is a well-off tech worker. Because lots of people can't meet for coffee twice a week to discuss cause prioritization or AI risk. Because $10 a week on coffee is just too damn much. Because Lyft rides are expensive y'all! Because $400 for a conference registration can be hugely prohibitive (a gigantic shout out to everyone who has supported the scholarship program!).

I hope that my uncomfortable declarations of my economic status lead more of us to be inclusive, and creates space for our group to grow into including more economic diversity.

Because diversity is good!

And low income donors give a larger percentage

*Please note that feelings of inadequacy expressed are not due to discriminatory acts of members of my group, or EA members in general, but are more accurately attributed to societal pressures and my internal dialog. In no way has anyone ever explicitly made me feel unwelcome, more that society tells us that our value is closely tied to our wealth.

Seattle Effective Altruist’s “Be Excellent To Each Other” Policy

A few people from the EA community have asked for a copy of the Seattle EA "Be Excellent To Each Other" policy (ostensibly our behavioral contract). Elizabeth posted it to her blog a while ago, but I thought it bore repeating. Mainly because I think it is a great group policy, but also because I think it is just an excellent piece of writing, and she deserves some good credit for it.

I think my favorite is the second paragraph.

It is the goal of Seattle Effective Altruists that all members feel safe and respected at all times. This does not preclude disagreement in any way, we welcome differing points of view. But it does preclude personal attacks, unwanted touching (unsure if a particular touch is wanted? ASK), and deliberate meanness. This policy applies to all members, but we are conscious that some people have traveled a more difficult road than others and are more likely to encounter things that make them feel unsafe, and are committed to countering that.

If you are wondering if something you are about to say follows the policy, a good rule of thumb is that it should be at least two of true, helpful, and kind. This is neither necessary nor sufficient, but it is very close to both.

If you find something offensive (including but not limited to: racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, ableist, etc) or it otherwise makes you uncomfortable (including but not limited to harassment, dismissal, unwanted romantic overtures), we encourage you to speak up at the time if you feel comfortable doing so. We hope that all our members would want to know that they have said something offensive. If you do not feel comfortable speaking up at the time, please tell a membership of the leadership (currently John, Elizabeth, and Stephanie) as soon as possible, in whatever format you feel comfortable (in person, facebook, e-mail, etc). Depending on the specifics we will address it with the person in question, change a policy, and/or some other thing we haven’t thought of yet.

If someone tells you they find something you (or someone you agree with) said offensive, you do not have to immediately agree with them. But please understand that it is not an attack on you personally, and quite possibly very scary for them to say. If you did not mean to be offensive, express that, and listen to what the person has to say. if you are a bystander, please convey your respect and support for both people without silencing either.

If you did mean to be offensive, leave. Deliberate personal attacks will not be tolerated. Repeated non-deliberate offensiveness will be handled on a case by case basis.

SEA is not in a position to police the behavior of our members outside our meetings and online presence (e.g. the facebook message board), and will not intervene normal interpersonal disagreements. But if you feel unsafe attending a meeting because of a member’s extra-group behavior (including but not limited to threatening, stalking, harassment, verbal attacks, or assault), please talk to the leadership. We will not have group members driven out by others’ bad behavior.

This is a living document. We can’t foresee all possible problems, or remove the necessity for judgement calls. But we hope that this sets the stage for Seattle Effective Altruists as a respectful community, and encourage you to talk to us if you concerns or suggestion

My additional two cents. Particularly when you are talking about controversial or sensitive topics.

Book Review: How to be Great at Doing Good; Part II - This is How We Do It

This is part two of my book review of How to be Great at Doing Good by Nick Cooney.

For better background please start with Part I

Reading the second part of How to be Great at Doing Good is like painting shellac over the top of the puzzle you just completed. You've invested time and effort into piecing together this intricate picture, and now you want it to stick - hopefully forever. The second half of this book reinforces and glues together all the little pieces we were working with in the first half. It adds some practical ways of overcoming the biases and cultural norms that hold us back from doing a lot of good.

In this chapter Cooney also introduces us to another premise [for previous premises see Part I]. While this one is only articulated explicitly a few times, it is another fundamental underlying belief of the author (and to many Effective Altruists).

4. All lives have equal value. Animal lives also have intrinsic value.

While it sounds similar to the Bill & Melinda Gate's foundation mission statement (because, well it is) the point made in this premise is a good one, and it sets us up well to discuss the second half of the book. We, as humans, have a tendency to favor taking care of those both geographically close to us, as well as most similar to ourselves (socially, racially, economically etc). Cooney goes into a number of studies that show how true and reasons why these preferences may exist. However, he sums up how this can be harmful succinctly when he states:

[W]e provide care to those who are in front of us at the expense of the many who are not... If our goal is to reduce suffering and increase well-being, it doesn't make much difference where on the globe that's taking place and who is experiencing it.

This one bias means that frequently we overlook the greatest amount we can do because the problem is far away or involves people not like us. For example very few US based charities look for opportunities to work overseas, where their resources may go much further in helping people in their cause area. This means that these charities are not prioritizing the cost per saving a life, but prioritize helping those closer and more like themselves, or more accurately, closer and more like their donors.

This preference directly impacts a charity's ability to do the most good because they are not looking at their bottom line. Part of this is because few charities examine their work from a data-driven framework. Cooney points out that charities rarely gather data on 'cost per' - mainly because donors don't ask for it. If organizations don't have incentive to collect good useful data they frequently don't. Often they feel they don't have the resources, there is to reason to, among many other reasons.

Does it seem strange to you that donors aren't asking for this information? It did to me too! But according to the Money for Good surveys only 6 percent of donors spent any time whatsoever on comparing the impact of different non-profits they donated to.

The vast majority said they do care about impact, and one-third of them said they would like to see research that compared different non-profits. But saying and doing are two different things.

That is the crux of it isn't it? Saying and doing are two different things. And doing things is hard. Comparing charities isn't just hard, it is intense, extensive, analytical, time consuming work.

Cooney proposes, what I think, is a very elegant solution! Charity brokers. The same way we have stock brokers than manage our money in the complex, confusing, data driven world of finance, we need experts in the field of charities available to donors. However there is almost no one out there doing this work. and of those that are out there less than 5% of them "recommend charities based on how much good they do." Egads! What are they recommending them based on?!

Unfortunately in the vacuum of charity brokers donors turn to things like Charity Navigator, and GuideStar. Both organizations do an important job of guarding against fraudulent organizations however their ranking systems are not based on how successful a charity is. Partly because charities don't make their bottom line data readily available so donors and these sites rely on what is available. Things like the number of members on their board and the amount spend on administrative and salary costs each year. Which is a terrible way to judge a charity.

So a lack of donor demand leads to charities not collecting data, or collecting the wrong data, which leads donors who are interested in data to turn to unhelpful and inconsequential information.

It is our job as donors to help stop this Catch 22. By requesting explicit clear cost-per breakdowns and bottom line data from our charities. By letting charities know we don't care about overhead or administrative costs. By donating our money as unrestricted funds and grants without limits or specializations. It is important as donors to request this information explicitly and consistently from our organizations.

And what about those of us that work at non-profits? How can we help stop this cycle? By collecting data! Cooney specifically points out how organizations should be running tests to determine the best way to do good. Frequently non-profits think that they lack the hours, man power, and money do run such tests, and that doing so would detract from the work they are trying to do. Cooney points out that by running these tests to find out what we don't know, to find out what works best, an organization can actually increase their ability to create impact significantly and make their money go further than they ever thought possible!

Why aren't we doing all this already?

Good question! Cooney points out a large number of reasons but since this is a summary I thought I would sum up four biases that stuck out to me while reading. These are four of the biggest obstacles we face when thinking about how to do the most good.

Bias 1: We prioritize people that are most like ourselves. Be it geographically, socially, racially, econ.... wait didn't we just read this? Ya Bias 1 is essentially a counterpoint to Premise 4. Again Cooney give lots of reasons for this, but what we are mainly concerned with is that we are predisposed to care more about those like ourselves. This means we dismiss out of hand things that could be potentially do more good because they help those far away, or different from ourselves.

Bias 2: We prioritize individuals over groups. We are more likely to feel sympathy for the individual person we pass on the sidewalk or a small child we see on a pamphlet than we will have a connection to a large group or organization. This means that often it feels better to give someone a dollar than give a dollar to an organization that could stretch it to help several people. It also means that when we see our money helped 20 people we still don't get as much of an emotional payoff as when we directly help one person.

Bias 3: We don't like change. It is that simple. We don't like change. We don't like it when our local coffee house rearranges their tables, we don't like it when policies at work change, we get scared and nervous about moving. We don't like change. It keeps charities from reevaluating their work, and it keeps us from changing our giving habits. It even stops us from thinking about changing our giving habits.

Bias 4: I call this the monkey see monkey do bias. Or perhaps more accurately money see money go. We think that because many people have done a thing it is clearly a good thing. We create our own social norms around giving. Lots of people give the the Salvation Army so they must be a good effective charity, because otherwise how could they have gotten so much funding and become so large? Unfortunately everyone else is subject to the same biases we are. And when it comes to charity work, income does not equal output.

And always remember: the goal of charity is to make the world a better place.

If we loose perspective of this, we will not be able to truly create change.

Protests - A Review of Join or Die Part 2

Originally I was going to have this be part of my Links from Last Week, but I decided I had enough to say about it to justify creating a stand alone post.

Join or Die Part 2 is a fairly good discussion about attending protests from an Effective Altruist standpoint. Frequently the argument is made that going to protests is a waste of time because it 1) detracts from more effective things you could have been doing, 2) is hard to track the results of, and 3) usually doesn't create results at all. I think Zach addresses these concerns quite tidily. With my background in politics & political science I appreciated his take on all this. I also appreciate him stating that we can (and in fact try really hard to) measure complex things like the relationship between political agency and impact.

I also think that his conclusion is sound. It helps that the conclusion is a resounding 'eh, it depends.' But what he states it depends on seems pretty true. A lot of what could make a protest or political activism useful has to do with emergence, which I think ties in quite closely with the EA idea of uncrowdedness. With the clear difference that the goal is to create more crowding.

The big problem it raised for me - which is something I continually have an issue with when EAs discuss using our time - is the assumption that someone's time could have spent working and earning more money. First, most people that earn to give do not work hourly jobs. Adding one hour of work time does not mean you get a set amount of extra money you wouldn't have otherwise had. And secondly, those of us that do work hourly jobs can't just show up to work willy-nilly and get more hours. "Oh that hour and a half I added to my time sheet? Yes it was on a Saturday at 3pm when we were closed, but I decided I wanted to earn a little extra money this week." Trust me, that shit don't fly.

I understand that this is used as a way to quantify time and how we can best spend that time. But every time it is used it feels like a blatant red flag that we are out of touch with the way most people function in the world. This bothers me.

Links From Last Week

My new desk inspiration

Excited Altruism

A great write up on how optimization, particularly for a good cause, is actually really exciting! Sometimes people seem to think being interested in effective altruism means giving up your passion. I've found the opposite to be true. My passion is helping people, optimizing for it feels more successful. The comparison to athletic mantras seems to fit well: "Athletes sometimes talk about “giving 110%” or “leaving it all on the field” – they can’t be satisfied with their effort if they feel they held anything back." This is what effective altruism feels like; it feels like not holding back.

Half-Assing it With Everything You've Got

Words cannot express how much I love this article. I particularly loved his analogy of homework. This theory and way of approaching school work is what got me through college. Most people looked at me like I was crazy when I explained it, so eventually I just stopped trying to explain.

"I personally find that shooting for the minimum acceptable quality is usually fun. Doing the homework assignment is boring, but finding a way to get the homework assignment up to an acceptable level with as little total effort as possible is an interesting optimization problem that actually engages my wits, an optimization problem which both my inner perfectionist and my inner rebel can get behind."

Robots & Basic Income

If you've never heard of basic income it is the idea that everyone is given certain basic amount of money so that they can exist happily in modern society. No job necessary. This seems pretty awesome to me, for a number of reasons, and I'm looking forward to talking with more people about the idea. This author talks about how technology is moving this closer to a reality, or even maybe an imperative.

Silicon Valley Philosophy

For those of you out there where philosophy and coding collide. Very funny.

Progress for Children

A photo story book from UNICEF. Beautiful photography paired with stats and achievements in helping children. A good reminder of why to give, and why giving makes a difference.

The number of children out of school has fallen from 106 million in 1999 to 58 million in 2012. But with population growth considered, if our rate of progress remains the same, roughly as many children will be out of school in 2030 as there are today.

Book Review: How to be Great at Doing Good; Part I - Why it Matters

Peter Singer's new book The Most Good You Can Do made a big splash in the Effective Altruism community. And for good reason; as one of the most prominent and vocal proponents of Effective Altruism Singer holds huge sway in the community and draws large amounts of press to the movement. While this book is still on my reading list, from what I've heard it is also one of the first books that lays out what EA-s believe (as much as that can be summed up). John described it as an anthropological view of Effective Altruism.

But in all the hubbub, the book tour, the excitement, and the press coverage I think there was a fantastic little book that was lost in the clamor. I have been amazingly impressed with How to be Great at Doing Good as a primer for thinking about charity evaluation. The author, Nick Cooney, brings some good street cred to the work - getting praise from Singer, Holden Karnofsky, and Adam Grant, being the founder of one of the most effective animal charities out there, as well as already being the author of 2 other charity related books.

I'm breaking my summary and analysis of the book into two posts. This one is for the first half of the book (Chapters 1-5 for those of you following along at home).

What I love so much about this book is its accessibility and gentle framework for thinking about assessing charities, and a primer for EA ideas in general. Plus the writing is upbeat, friendly and approachable. Most EA writing is dense, academic, technical, and can come off as... well a bit cheeky at times. So this book immediately struck me as a great one to hand out like candy to anyone curious about gauging charities.

Cooney uses three basic premises to inform most of his discussion in the first few chapters (and beyond). Because these fundamental ideas permeate the entire book let's spell them out now and make future references simple.

- The purpose of charity work is to reduce suffering and increase well being

- Giving to charity, in any form, is a selfless act, and not something done for personal gratification (though it is a fringe benefit)

- Where we work, and where we donate, inform our sense of identity and self-esteem

While 1 & 2 are laid out clearly (and referenced often) the third is stated explicitly only once or twice, but is a pervasive undercurrent throughout the chapters. Indeed, it is this premise that makes the book more accessible; particularly to those of us that have spent our careers in the nonprofit world or donate large sums of money. While as premise 2 states, we don't do charity work for personal gratification it is a side effect of the work, and it becomes emeshed with our life satisfaction. Throughout the introductory chapters the author points out to his readers that we should view analysis of our work and our donations "not as threats, but as opportunities."

It is through premise 1 that Cooney encourages us to consider the bottom line, not the umbrella of a mission statement, but the true purpose and goal around reducing suffering, and increasing well being. It is through this that we are then able to compare charities and how effectively they complete their work. This emphasis on the 'bottom line' is rarely promoted in the charity world, but is something that is necessary to create real change.

Cooney makes the argument for bottom line thinking and comparisons with a compelling fact:

"The average American does about 20 hours of research & comparison-shopping before buying a new car. How many of us spend the same amount of time researching & comparison-shopping before choosing which charities to support? The fact is that our charity decisions are far weightier than our decision of whether to go with a Nissan Altima or a Toyota Corolla."

There are real lives (potentially many lives) that are saved or significantly impacted by our donations, so we should be taking these decisions very seriously and give them the weight and brain-space they deserve. So the success of charity matters, and we as volunteers, workers, or donors should care about it. Why? See premise 2.

We have the why of evaluation, now to address the how. It seems easy to find charities that meet the definition of charity (premise 1) but comparing vastly different goals can feel like an impossible task. Cooney points out that we actually do this all the time. Deciding whether to donate Greenpeace or the Tea Party is usually an easy decision for most people. It doesn't matter WHICH choice they make, only that it is usually clear to people which bottom line they prefer. It is with this same heuristic intrinsic knowledge of our values that we can put real numbers to comparing charities.

When faced with two charities that have different bottom lines ask yourself a simple question. How much outcome/bottom line would charity X have to provide to get your $100 donation vs the other charity? Put another way: suppose you have a desire to give to charity X, but before you do you are comparing them to charity Y. Charity Y currently achieves its bottom line 1 time for $100 and charity X currently achieves its bottom line 100 times for $100. Because you prefer X, you believe it does more good - in fact, you believe it does ten times as much good. So ask yourself: how many times would Y have to achieve its bottom line for $100 for you to prefer that charity? Suppose you decide that Y would actually have to provide 200 of their bottom line before you would consider donating to them over charity X. So actually you think X does 200 times as much good! That gives you an idea of how many times better you think one charity is compared to the other.

By asking yourself how many times Y would have to achieve it's bottom line before you would decide it is as efficient or more efficient than X, you can assign a numerical value of how efficient you believe one charity is vs another. Their bottom lines may be different, they may be saving animals, or hiring actors for the local theater group, or curing children of TB. The point is you can create a simple heuristic comparison that allows you to figure out what charities you consider better at achieving their bottom line, and how important that bottom line is.

Feeling uncomfortable with this? Cooney would gently refer you to premise 2.

Wait, wait, wait wait!

But I LIKE saving bunnies, I LOVE donating to the ballet, I get deep meaningful satisfaction out of volunteering at the food bank.

That is AWESOME! Don't stop doing those things. You don't have to stop giving to those places. Only re-consider calling them part of your charitable giving. Instead call volunteering what it is - a way to feel warm and fuzzy about yourself, a way to feel like you are participating in your community. Budget the ballet donation for what it is - entertainment. It just comes out of a different budget line. Why? Because the suffering you are reducing is your own (premise 1 & 2 double whammy). And that is a good thing! You shouldn't suffer! You should get your warm fuzzies (props to Elizabeth for the phrase I'm stealing); just don't expect to find them while you are changing the world.

So what holds us back from adjusting our spending and doing? Cooney lays out a few simple psychological barriers:

- Lack of exposure to the idea. We aren't encouraged to think critically about altruistic gestures

- We want to keep things the same. We are naturally adverse to change, in our own lives and habits as well as in organizations

- We have a natural preference to help those most similar and in closest proximity to ourselves. This means we can overlook potentially huge good we could do elsewhere

- It is just easier not to. It is challenging to think about comparing charities and frequently we turn to charity work to get away from bean counting

- The best and most effective thing isn't always glamorous, interesting, or emotionally gratifying

Luckily he also provides us with a few ways to overcome these barriers:

- Give yourself space to think. This is hard work, guys! Give yourself room to think, be wrong and reevaluate.

- You are allowed to be human! Of course you have emotional reactions, follow your intuition, and act on instinctual empathy. Though perhaps this is done best in other areas of our life (premise 2 again).

- Remember the bottom line. Keep in mind that giving to one organization vs. another can ultimately mean saving 1 life when you could have saved 10. And lives are important.

This Year's Charity

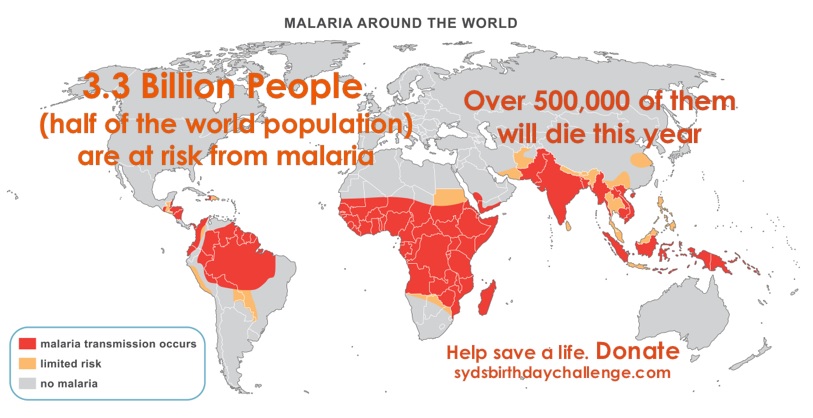

This year I am raising money for The Against Malaria Foundation. One of the major symptoms of this deadly disease is fever, so this year's element will be fire.

Our goal is to raise $2000 which will go to provide bed nets for those in areas impacted by malaria. The best way to protect pregnant women and children, those most impacted by the disease, is through preventative measures like Insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs). As part of this challenge I've chosen to support those organizations that have proven to be more effective than other charities. AMF is able to provide each net for a total coast of just $6 each.

That means if we reach our goal over 300 people will be protected from malaria.

Not only is this an amazingly inexpensive way to save a life AMF is rigorous when it comes to tracking their nets; making sure that nets are distributed to intended recipients and tracking their use over time. They are one of GiveWell's top rated charities and GW has looked into their organization extensively. You can read all about them on the GiveWell evaluation page.

To support this year's fundraiser, please donate below. You should can share the message! Check out my resources page for easily sharable materials to spread the word.

Diversity: Why it is particularly hard to talk about in EA

Please note that this article is not a theory to solve all problems of inclusion. Nor do I think that my views expressed here are a sufficient means to inclusion & diversity, simply that representation is a necessary step. I am hesitant to publish this article because of it's sensitive nature.

There have been a series of discussions on EA forums about representation of minorities and marginalized groups. I will be writing several posts about this topic.

There has been a lot of chatter around the EA forums lately about being welcoming, inclusive, feminist, diversity etc, etc, etc. But recently I got to have a brief encounter with someone in my EA group that brought to light some of the reasons this is particularly odd topic for EA.

I believe that many people take it as a matter of course, or have been trained to STFU, that diversity is a Good and Virtuous aim. A lot of Effective Altruists have come to the community through things like LessWrong & Center for Applied Rationality (CFAR) which promote rationality and clearer more logical thinking. Which makes total sense! EAs are trying to make rational, deliberate choices around the best way to improve the world. And as J pointed out, EA is an easy way to feel like you are applying the rationality skills you learn.

So to be involved in the EA movement to some extent you touch on, if not get wrapped up in, the rationality movement. One thing I've noticed hanging out with a bunch of rationalists is that they have a desire, and have trained themselves, to question and analyze ideas, to poke at them and follow them to some sort of conclusion. All ideas. Particularly ones we take as a matter of course.

Enter diversity.

Have I made you uncomfortable yet?

No? Let me explain with my experience referenced above. During our last meet-up, and having been thinking about diversity and inclusion in relation to EA I looked around the room. Not too bad. We have several Latinos, almost a 50/50 split of women, several Asian members, and a few people who would identify as Queer. Good representation of Seattle demographics except... oh wait. We're all white.

I don't mean Caucasian, I mean the physical complexion of the group was fairly uniform and fairly... fair. Part of this undeniably is because we live in the PNW and don't know what sunshine is. But mostly it is because we just didn't have anyone of a darker complexion in the room. Beyond that everyone was college educated and a programer (myself excluded [more to come on that later]).

After the meeting had concluded and there were a few of us left chatting, I brought this up. Another member paused, looked at me and asked why I thought it would be of benefit to the group to have or recruit members who are specifically of a different complexion. It took me a few small moments to collect myself and remember the social context of the people I was with - I point you back to paragraphs 2 & 3. She asked not out of internalized racism but out of a desire to test my thinking and the rationality of my argument.

My response followed basically this premise:

People of different physical attributes experience the world differently. Both because of the potential prejudice they face, and due to historical systemic inequality. Having disparate life experiences creates different ways of looking and understanding the world which informs new ways of thinking. EA could benefit and be strengthened by incorporating and being cognizant of various viewpoints and ways of understanding.

This seems sort of logical to me. But we aren't going for logical, we are going for rational so..... link, link, study, study, study, findings, and findings. As most of the data in the articles listed show, it is not enough to have diversity for diversity's sake; to improve performance and potential of a group it is important to have a diversity of experiences and perspective. It seems unlikely that we will have a diverse number of perspectives with a group that is generally homogenous in terms of outward racial identifiers.

For a wonderful example of how this argument can be problematic see this article by Nonprofit with Balls (whom I love).

This member and I also briefly discussed color being a 'stand in' word or identifier for economic differences. And while I think these can be related, I also think they are distinct. Again more on that later.

What I failed to mention that day and what I think slips so many people's minds is also a very simple truth: those that benefit from the most effective charities, the world's ultra poor, are disproportionately people of color. And how can we be a movement that serves this demographic, and clearly states our goal is to avoid white knighting if we can't recruit people of color?

10% of Harvard Donation

John Paulson, a wealthy hedge fund manager just donated $400 million to the Harvard School of Engineering, which will now bear his name. I have a hard time imagining how exciting it must be to get that check! To be able to cut that check!

But now that I'm thinking about it, I'm not sure an Ivy League school would be my first choice. Or even my second. I'm not the only one to think this. Author Malcom Gladwell had a rather poignant quote on Twitter, and Vox had an article earlier in May along the same lines.

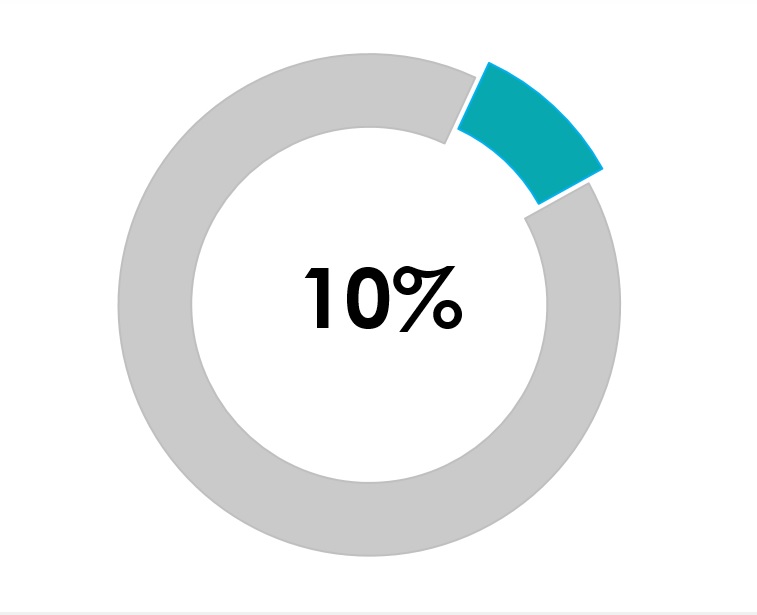

So I wondered what could have been done with just 10% of his donation if it had been given to a highly effective charity? Harvard still gets $396 million (nothing to sniff at), John probably still gets the department named after him, and a nonprofit can make a huge difference in thousands, or millions of lives. So what is that other $40,000,000 really worth?

Here is the breakdown if just 10% of that had gone to any one of these highly effective charities:

- 50,000,000 children protected from schistosomiasis for one year by SCI

- 400,000,000 children dewormed, or 4,444,444 people provided clean water for one year by Evidence Action

- 36,000 households funded (averaging 5 people each) by GiveDirectly

- 24,096,385 people protected from malaria or 11,986 lives saved by the The Against Malaria Foundation

- 26,666 schools built, or 222,222 hand washing stations, or 400,000 latrines built by Oxfam

- 1,355,200 women transported, or 75,288 complete reparative surgeries completed by Fistula Foundation

- 800,000 people cured of blindness via surgery, or 266 rural hospitals built by The Seva Foundation

- 153,846,153 people provided with micronutrient food fortification for one year by Project Healthy Children

- 1,600,000 people given high quality healthcare in rural Nepal by Possible

- 2,250,984 years of healthy life provided by Population Services International

Any one of these things could be done with just 10% of his donation. Just 10% for what he already allotted to give away anyway.

Numbers via The Life You Can Save's this nifty charity impact calculator

The Power of a Purchase

I grew up with parents that bought from local organic before it was a 'thing', who explained the implications of spending more money on Fair Trade coffee, and who insisted on washing and re-used our sandwich bags to cut down on our plastic waste. BTW my classmates in elementary school thought I was really odd, and a bit of a know-it-all - thanks mom. Part of what I was taught early is that ultimately we vote with our wallets. And I still believe that to this day: how I spend, even more than how I act, directly impacts the future we invest in as a society.

So recently I've been wondering about the difference between $1 spent on a Fair Trade item and the $1 donated to a good charity. Giving What We Can posted a blog post about this that got picked up by the Huffington Post. I love that effective thinking, living, and giving are getting so much coverage lately. That being said this article didn't ask my most basic question - how can I best cast my vote?

While I'm glad people are thinking about this I didn't seeing a real direct dollar-to-dollar comparison. Yes $1 can deworm two children and I know the benefits of that, but it seems like it is very hard to break down the economics of that $1 spent on a more expensive bar of chocolate that is Fair Trade.

I also agree with another commenter who mentions that my decision to buy FT goods isn't about charity, it is about fairness. I believe that people should be paid a sustainable wage, as a bare minimum. So I am also inclined to separate what I give charitably from what I spend on groceries. I buy FT not as a way to donate to a cause but because I think of it as a basic obvious truth that people should be paid fairly, therefore things cost more. This budget is separate from the budget I use to make the world a better place. FT is about doing good, donation is about striving for better than good.

That being said, I would be willing to change this behavior/ideas if there was a clearer way of comparing the two. Perhaps comparing the percentage given to improve production compared with the impact of the same money going to an effective agriculturally focused charity? Again the economic outcome of buying Fair Trade seems fuzzy and hard to track. Hopefully someone smarter than me is willing to run these numbers because I would love to know what they are.

I think there is also something to be said for feeling good about the products you are buying, and making conscious choices every day.

Welcoming

Effective Altruism and It's Intersection with Traditional Social Justice

There have been a series of discussions on EA forums about representation of minorities and marginalized groups. I will be writing several posts about this topic.

One conversation that I found particularly of interest was in the Women in Effective Altruism group. While the conversation was broad, the topic/question originally posed was about the intersection of feminism, progressive thought, social justice, and the 'new kid on the block' EA.

Below is my comment* in the thread.

This is a great conversation to be having and thank you for posting! One thing I am continually re-discovering is how often causes focused on more measurable outcomes - things like hunger, poverty, education, and health - turn out to actually also be women's issues.

By supplying clean water to a village I've created space for young girls to go to school and their mothers to be more empowered. By deworming children, girls are better able to learn which leads to better health and autonomy. So in my mind EA is a deeply feminist movement, whether we talk about it explicitly or not. Frequently it is difficult and 'messy' to try to discuss, let alone quantify, things like power dynamics and systematic marginalization of groups. So instead of trying to tackle these complex tangled issues head on, EA takes the approach of easing suffering through low hanging fruit. No woman can become empowered, or flourish if she has died from malaria.

I believe that this approach also helps us avoid 'white knighting.' I think by preventing deaths and easing suffering we are better able to be a support for those living in poverty and in situations and cultures vastly different from our own. Anecdotally I am less comfortable supporting an organization that tries to tell a woman in sub-Saharan Africa how to address her marginalization. I do think it is reasonable to give her a cash transfer and let her decide how to empower herself. Again the goal being to address the larger issue by tackling a smaller, more measurable, manageable outcome.

Having said all this I think it is important to note that in my experience most EAs do not take the work of older SJ movements for granted. It is through their research and experiences we are better able to understand our complex world. I don't think that questioning efficiency is intrinsically a negative judgment. It's a question.

EA can at times come off as 'not listening' because in general the people drawn to EA are passionately curious. We want to KNOW. A request for more data, a push to explain yourself, a request for evidence, particularly from someone pale and male, can seem dismissive and flippant. When really in many cases it is an excitement to learn about an issue that someone is deeply invested in. It is this desire to verify and maximize that can come off as cold, but it feels important to do this despite it being uncomfortable at times.

I hope we've been able to demonstrate a little bit of the listening and sharing you were hoping to find. I would love to read your article when it is finished. Would you be willing to post the link here? context: the person asking the question disclosed she was writing an article for Mother Jones. I'm excited to read & share what she writes.

*Note that I have taken out names to protect anonymity since this is a closed group